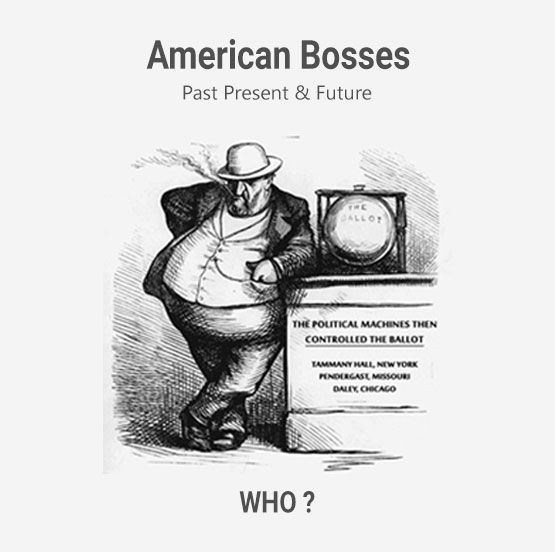

American Bosses

Past Present And Future

Who?

Copyright 2016 by WeleadUSA

All Rights Reserved

![]()

In these pages the WeLeadUSA contributors propose a comprehensive solution to our nations many political and social dysfunctions in the form of the Citizen’s Access Network.

This network, and the strategy that makes it possible, will provide what has never been available to any people, anywhere at any time; unfettered access. Access to each other, access to our elected officials; our constitutional agents, and with them, access to our government beyond!

Our system is a decentralized republic that from the beginning was based on electing representatives; and lots of them. This means that the relationship between the people and their governing bodies are dependent on the election – the electoral system – as the ultimate means of enforcement and regulation available to the people. So, if that mechanism was improperly structured, or executed, obviously, trouble would be sure to follow; and follow it has.

Yet today – after 200 plus years of running this republic, framed on these electoral realities – we still lack a definition of what a meaningful election should be; nor have we even attempted to apply any kind of standard to our only means of public control.

Therefore it should come as no surprise that despite the attention paid to the subject of political relations and the elections that must express them, the remedies offered have been faulty, redundant, paternalistic and failed; with one very notable exception.

Yes, the correction has been made and the tools exist, if we will consider our problems more holistically.

If we do, it will become clear that access born of proximity and unquestionable power can end our historic political-civic relations based on fixed hierarchies of “leadership”, with its limited transparency and poor record, and be supplanted with a model of public partnership based on our established constitutional principles and foundational traditions.

This can be accomplished by the capable people leveraging three core pillars; assets and actions available for immediate and powerful use.

As this article attempts to clarify, we should revere the work of our founders for one good reason at least. For all of their flaws, more recent controversies regarding their motives, and the inequities of their time, after 230 years plus, we can’t say they didn’t give us a chance!

The country they forged became quite successful, quite powerful, and so it might be easy to look back and consider the result to have been inevitable; but this would be incorrect. There were so many obstacles to overcome that they may have on occasion thought that “vanquishing” England was the least of it.

For example, agreement among men– not to be confused with unity – is perhaps always in much greater supply than imagined but capturing that agreement, and putting it to use is another story. Tensions born of that process can create what we might today call polarization.

Many so-called polarizing differences of issue and mind – as momentous and terrible as slavery – were present yet did not stop these men from capturing their agreement on the need to create this nation; whether through the waging of war or politics.

We make much of polarization today but the politics of the framers time, and beyond, were quite polarized and vitriolic.

The men who came together at the Constitutional convention in 1787 came from disparate colonies of what was then a loose, far-flung association of states that sometimes operated with great difficulty under the articles of Confederation. They could hardly be classified as unified but questions of trade, management of the war debt, monetary policy, and relations both foreign and domestic, all made their contributions to the convening of this body. It was clear that in order for the promise of the revolution to be fulfilled – and the ambitions of the founders realized – a cogent nation must emerge from these distinct and occasionally polarized territories.

However, it would be the grounded search for – and the seizing of – agreement and settlement that would be decisive; not demands for an impossible unity.

That process began in May 1787 as fifty-five delegates from those 13 colonies – covering nearly 500,000 square miles – arrived in Philadelphia to begin work on what would become the U.S. Constitution; the nation’s legal and moral framework that remains central to our identity to this day.

With some irony, it was essential to the work of the convention that a fairly polarized group of framers had to deal with a prevailing concern of what was then commonly called faction. Driven by fears stemming from the “untempered will of a provincial majority cobbled together from dangerous factions of special interests”; this was a problem that required great care.

Though their anxieties regarding faction have been interpreted differently through the years, there is no doubt that issues of property rights and the balancing of power was central to this question. With the circumstances and effects of Shay’s rebellion an important element to the calling of the convention, managing the levers of political power — that would either protect or overthrow those rights — was much on the mind of those defending the Constitution and advocating its ratification.

Concerns regarding partisanship and political parties are also generally accepted as integral to these deliberations. The problems of mischievous faction — and the corruption it was sure to bring – as well as balancing power to ensure the rights of populations “whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole” are reflected throughout the framework of the Constitution; including the Electoral College a very carefully crafted answer to the problem.

This framework thought the problem through mostly as a matter of balancing competing interests. This balance depended upon three things primarily:

A difficult act to balance to say the least and, although success of this model can certainly be claimed, the tensions endure. Considered from another point of view, an overarching goal to control factions could be interpreted as an effort to create some sort of defacto unity or, as some have argued, an incoherent and ineffective structure likely to benefit

those most organized; which many would argue is exactly what we see today.

In any event the framers well understood that even within related groups, differences of mind, body, and experience – being part of the human dynamic- would be present and difficult to manage and this was true of the very group and experience they were part of.

In any event the framers well understood that even within related groups, differences of mind, body, and experience – being part of the human dynamic- would be present and difficult to manage and this was true of the very group and experience they were part of.

This can be seen most everywhere; a good example being our major religions. There, a core tenet is acceptance by all members, yet differences feed a tendency towards faction that can create many sects within the overall group. In the United States alone it is thought that there are some 1,500 Christian denominations and perhaps as many as 39,000 worldwide. The tiny population of Jews still managed to divide themselves into seven separate sects. Islam has something on the order of 45. No doubt many of these schisms were born of relatively earthly matters.

The fledgling republic had no more immunity to such tendencies than in these cases and quickly the lines of polarization and faction began to blur– embodied in the differences between the antifederalists, skeptical of the constitution, and the federalists who pushed hard for its ratification.

Once the new system was adopted these polarizing differences manifested factional expressions (in the sense of politics and political parties) in the persons of Thomas Jefferson, anti-Federalist (Democratic-Republicans), and Alexander Hamilton, Federalist; two men of extreme polarity.

Hamilton, with his belief in a powerful central government, thought that the war debts of the several states should be repaid by the new federal government. He also advocated for aggressive action regarding internal improvements and the creation of a central bank to assist in managing that and as well the nation’s overall monetary and economic affairs.

This was in great contrast to the sensibilities of Jefferson who worried about the unwarranted accumulation of centralized power. In his “debate” with Hamilton, he denounced the bankers and stock jobbers who, with their speculation and greed to own the supply of money, would surely trigger a loss of the liberty that was so recently and hard won.

So, even amongst the core group who agreed on the desirability of a national government, there would be no unity but, there would be faction; demonstrating that passions so innate to human behavior and endeavor be it church, state, family or friend are not going to be so easily tamed or balanced. (Despite the agreement, the settlement, the two men ultimately came to of consolidating the war debts and the creating the central bank in exchange for locating the Capitol on Southern territory)

So, even amongst the core group who agreed on the desirability of a national government, there would be no unity but, there would be faction; demonstrating that passions so innate to human behavior and endeavor be it church, state, family or friend are not going to be so easily tamed or balanced. (Despite the agreement, the settlement, the two men ultimately came to of consolidating the war debts and the creating the central bank in exchange for locating the Capitol on Southern territory)

However, whatever the angst and anguish – then and now – studies of evolutionary biology do indicate a substantial benefit in such “groupish” behavior. Perhaps this inclination for polarization or faction might be more useful and not quite so negative a trait as the framers thought; or we think. As pain in the body signals important information

that something is amiss; so too does the threat – or perception – of faction signal where and how we must focus attention.

With the benefit of hindsight we can see that perhaps opportunities were lost by attempting to stamp out what could not be stamped out at the expense of other approaches. And here a pivotal consideration emerges that drives both the problems and opportunities of the American system to the present moment:

Although that would not and could not have been the mindset of the framers given their background and era, the question would take center stage; and stay there.

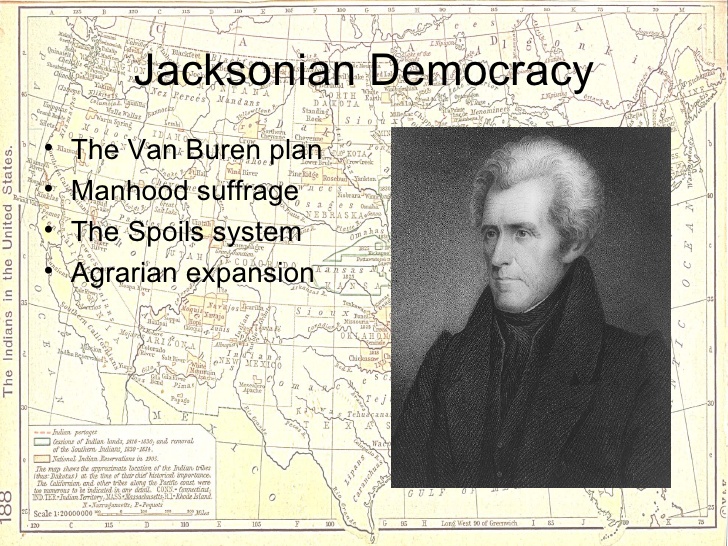

With the passing of just a few more years – in what came to be called the “Age of Jackson” – and taking its cue from the founding generations divides – faction would manifest its modern character in the form of the two-party system in an ever more expanding, and raucous, electoral environment.

The election of 1824 brought John Quincy Adams to the presidency, with what the supporters of his opponent Andrew Jackson called the corrupt bargain. Adams lost the popular vote, but with no majority in the Electoral College, was confirmed as president by the House of Representatives.

This was a pivotal event that fueled a more formalized party politics. This in turn facilitated the emergence of our rather unique two-party system as a more populist national mindset led to the easing of voting qualifications and participation; a feature of that “unplanned expression” of an evolving democratic process.

The subsequent election of Andrew Jackson as president in 1828 catalyzed the formation of the Democratic Party and made Jackson’s presidency a defining moment in the evolution of the American political system. The campaign of 1828 was crucial to the development of a two-party system – and our modern system of politicking – as presidential electioneering and electoral politics at all levels took its more contemporary form. This, as the country’s business was now being more visibly processed through the two parties; then the Whigs,

basically considered the heirs to the Federalists, and the Democrats, the successors to Jefferson’s anti-Federalist Democratic Republicans.

Under the sway of Jackson’s fearsome personality there was also a strengthening in the power of the executive branch and many lines of polarization – still with us today – were drawn.

Though occasional third-party challenges and movements were seen – expressed particularly in presidential elections – the major two-party approach continued to solidify and has remained at the heart of the American political system.

Naturally as a result of these dynamics, strong party organizations began to take form and with them the machinery and hierarchies necessary to run such large, complex organisms. Such features; more of that unplanned democratic expression, may be innate to a process of great growth and experimentation and should not, in the immediate anyway, be thought of solely in the negative terms of faction or corruption.

Given the proper concerns of the framers it’s quite understandable they may not have been able to foresee (or reconcile) that a growing country – a republic based on the election of representatives – would require the means to filter and clarify the mind of the public. Without some form of political organization – platforms and other means to draw distinctions and organize around them – how could a vast and diversified people be accurately represented?

However, the problem this presents is revealed more by the question of power – to whom it is distributed and how it is used – rather than a simple condemnation of faction as we will see.

In any event, the growth of the party machines were particularly felt in

concentrated urban areas where the political machines and its bosses would seek out and demand loyal supporters who would serve the interests of the party.

Those interests began with winning the elections that determined public policy. Of course attached to the power to enact policy is patronage – and the power to distribute it – which unfortunately is quite encouraging of corruption. Jobs, lucrative contracts, career opportunities– who got them and what was gained in the exchange all hung in the balance as the parties and its machines won and lost elections in their struggle to influence the public and gain supremacy.

However, all that was at stake in this ‘spoils system’, as it was known, hinged on the central power these machines and its bosses wielded; the power to control access to the ballot. With this control, they alone would determine who would stand for — and thus likely hold — elected office. This would ensure that the allegiance of the constitutional agents running, and being elected, was owed first – perhaps solely – to the party and people responsible for nominating them; not the citizens who voted for them.

However, all that was at stake in this ‘spoils system’, as it was known, hinged on the central power these machines and its bosses wielded; the power to control access to the ballot. With this control, they alone would determine who would stand for — and thus likely hold — elected office. This would ensure that the allegiance of the constitutional agents running, and being elected, was owed first – perhaps solely – to the party and people responsible for nominating them; not the citizens who voted for them.

It was there; right there, that the merging of faction to corruption in this system was assured.

As unexpected and extraordinary powers devolved to remote people and processes, beyond the reach or understanding of the public, the game would be for spoils and power and not considered deliberation of principled differences.

Despite the solidification of the major two-party system, these parties from time to time were subject to realignment- with some six being counted over the generations. Prior to the last of these realignments, the parties’ asserted their iron-grip control through the apparatus of ballot access and party nominations; the foundation of any hopefuls attempt to seek elected office.

Dog catcher to president; that access/nomination must first be secured or there could be nothing; and that meant a binding of candidate to party-machine in an unshakeable trust.

The political machinery – the bosses, their friends in industry and beyond – with this trust; this absolute grant or deny power, were able to control the “public sphere” – by proxy.

This because:

Given the nature of this power-structure what would be delivered would be exactly what the machine demanded.

With no question as to who a whom their allegiance was owed, a quid pro quo relationship was unavoidable and much more than “an appearance of corruption” was the norm.

Though it could be argued that the human dynamic makes these outcomes inevitable, and that there were important accomplishments this system could claim, its downside was substantial. The prizes of graft; the lucrative contracts, the no work jobs, the pensions, the skims – these were no doubt the least of it.

But whatever their nature, all the distortions of public policy first were enabled by the power to control ballot access; a power only the party machinery could wield. Naturally, as a result, our republic was substantially in the hands of this machinery and those who channeled its power. Just as the framers had feared, however unexpected or unforeseeable this expression of it may have been, faction and corruption ruled.

But whatever their nature, all the distortions of public policy first were enabled by the power to control ballot access; a power only the party machinery could wield. Naturally, as a result, our republic was substantially in the hands of this machinery and those who channeled its power. Just as the framers had feared, however unexpected or unforeseeable this expression of it may have been, faction and corruption ruled.

Nevertheless, this sorry state of affairs would allow their work to be put to the test and answer the crucial question; would it give us “that chance”?

This corrupt state of affairs was unacceptable to many and reforms were pursued.

Inherent to this pursuit was the question of whether the extraordinary framework the founders created – meant to establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty – could provide a solution.

Could it accommodate an ongoing, evolutionary and unplanned democratic expression; but one now required to push back and reform the distortions of power, faction and corruption permitted by previous unplanned expressions?

The movement that would answer this question — and attempt a pure realignment —began.

Drawing support from an urban, college-educated middle class, the progressive era reformers – circa 1890-1920 – sought to eliminate this

corrupting synthesis of party and government from our democratic processes. Testing boundaries, they also fought to curb abusive business practices, force management to address the hazards that plagued the of health and working conditions of its labor, and consider matters of the environment.

In civic matters they fought to get an apathetic public more engaged by giving them more authority over government through mechanisms like the direct election of senators, ballot initiatives and referendum, and recall elections. With the women’s suffrage movement central, great change swept through America and though its nature and aims were very different, it was no less a radically transformative time than the revolutionary era.

This broad movement also saw controversial failures; most notably prohibition. It is therefore understandable that amidst this upheaval of social change and democratic experimentation – and dearth of alcohol – the importance of another reform of this period could easily get lost and its vast implications largely overlooked. This was the extraordinary accomplishment of making access to the election ballot open to all, and passing – eventually in all states – the reform of the direct primary.

This reform took the absolute power to control ballot access and party nominations from the party bosses and machines and gave it to the American voter.

This reform took the absolute power to control ballot access and party nominations from the party bosses and machines and gave it to the American voter.

As we have seen, this was the pivotal power from which all else flowed. This meant that also given to the American people with this change was the potential to reverse deeply rooted power structures within government and society; an opportunity difficult to imagine today.

It also provided conclusive proof that the “chance” the framework provided its people to establish, and when necessary, renew their republic was indeed genuine. However, keeping that republic is quite a separate task so that part of the equation would once again have to be put to the test.

“Very few other countries use party plebiscites to nominate their candidates, but the United States has employed primary elections widely for nearly 100 years”.

Now for the first time – anywhere – the power to control access to the electoral ballot and nominate was firmly in the hands of the American people.

As to the parties and elected officials, this was a pivotal change that of course demanded caution. They were wary in their approach to this new, unknown arrangement and likely encouraged participation tactically and with great care. They coped fairly well through this transition period however as their influence remained strong with the last vestiges of the machine system lasting into the 1960s, and in some places beyond.

As to the public- despite some early success – participation in the nominating process and turnouts in primary elections declined steadily and mostly have remained at very low levels in terms of both participation and awareness. Thus, the profound shift in power relations this reform made possible produced little fundamental change.

Interesting and unfortunate to note in all of this was that as a momentous, highly unlikely experiment of historic proportions unfolds – and fails – little public reflection on the events can be found. A society overthrows an entrenched, corrupt, powerful and essentially ancient system; hands its central power over to the public no less, sees that experiment fail; and yet hardly a peep about what happened or why can be heard?

Perhaps these few questions would have been a place to start!

Primary elections have been a prominent feature of U.S. politics for the past century. However, surprisingly little is known about how primaries have operated over time. Except for the most recent decades, we do not even know simple facts such as how many primaries were contested, how competitive the contested races were, and how these patterns varied across states, races and time. This is mainly because of data availability [lack thereof].

Unlike in general elections, the main political parties do not exert oligopolistic control over access to the ballot and do not structure the choices of voters through well-established brand names. Rather, any candidate who can secure sufficient numbers of signatures or pay the appropriate filing fee can get on the ballot.

If such reflection were sought we would have to come to the conclusion that only the people at large; free of special interest, conflicts or some manner of entrenchment, could be depended on to seize this opportunity. Clearly others will not, and by failing to understand this

– and the chance – they are ultimately responsible for this profound failure.

Compounding the failure was that while this most powerful invention – one likely only the American system could produce – made very little lasting impact of the kind intended; it did have an immense impact of the kind unintended.

“The price of liberty is eternal vigilance”; so said Thomas Jefferson and certainly the idea of vigilance was the intention behind this reform. The progressive reformers pushed this unprecedented, unplanned expression of democracy as the way to undercut the power of local and state political machines and with that bring into the process and parties fresh candidates, new ideas, and coherent, organized constituencies.

“The price of liberty is eternal vigilance”; so said Thomas Jefferson and certainly the idea of vigilance was the intention behind this reform. The progressive reformers pushed this unprecedented, unplanned expression of democracy as the way to undercut the power of local and state political machines and with that bring into the process and parties fresh candidates, new ideas, and coherent, organized constituencies.

This, because it was understood – even if only vaguely – that only popular elections for ballot access/nominations could produce a genuine, principled, electoral landscape – as opposed to a far too little and late Election Day.

Alas, these goals were not achieved. Wherever the finger of blame for that unhappy outcome might be pointed, what clearly did happen was that the “professionals” learned to manage the new reality. That reality brought a new kind of machinery to bear; more of the boardroom than the smoke filled room.

A clever label, the Money- Media- Election Complex, captures well the idea of this modern model of political-social control that has emerged supreme. With this complex added to our list of complexes, one could say we developed a complex that has manifested the dysfunctions that today we are so familiar with; a very consolidated yet very fragmented, ineffective media, entrenched incumbency, revolving doors, endless wars, economics that beg bankruptcy, and bitter social concerns of doubtful character.

Fully matured however this machine – unlike its predecessors – is “not of faction”. No! But, by exploiting its divisive dynamics for its own benefit only, it has taken American politics and its issues of corruption, globalism and social division to the next and perhaps fatal level.

Over time this latest realignment transformed many of the methods and assets of the old system into its modern equivalent. Party discipline – a major feature of the boss system – gave way to candidates more dependent on donors, and other “policy demanding” players rather than a party apparatus itself. These donor-demanders fully involved themselves in the nomination process thereby becoming integral to and within the party. No longer was a formal rise through a party hierarchy necessary to attain influence and power; now, the clever use of modern electoral tools would be sufficient.

The parties, though substantially diminished in raw power, still remained important, coordinating the trade of this complex. For the public, with ballot and direct nomination reforms in place, electoral-access was now technically available to anyone capable of meeting the requirements; this served to change the role of the major-parties to that of a regulator.

By recruiting and “front running” candidates who are more likely to fit the mold of fundraiser and cooperator, their job in – and for – this complex is to assess, filter and limit. So, what determines “electability” in the minds of the complex is the candidate’s capacity for and willingness to raise money (or their own personal wealth) and of course

play ball.

This has served to homogenize the profile of many elected officials; for instance there is about a 50% chance that a member of our federal Congress is a millionaire. The average net worth of members in Congress is a bit more than $6 million, while the median net worth is $1 million. Further, while some 54% of Americans are considered “working class” only 2% of the members of our federal congress come from that background with percentages at the state and local just as low. Clearly, money has become a defining factor in our system.

However, with electoral advantages born of redistricting limiting competition and favoring incumbents in general elections – thus ensuring safe seats for one or the other party – we might want to ask why this is the case.

In other words, if a seat is safe, why would the money be so important?

In other words, if a seat is safe, why would the money be so important?

The answer can be found in the nomination process where great disruption would be possible if the intent of the primary voting reforms had been achieved and eternal vigilance enabled.

Genuine competition for ballot access/party nominations to stand for office would ensure unregulated discourse – a medium – that is necessary to a genuine republic and self-government; which is not possible in a controlled environment where principled differences cannot contest.

Through mass media, technology, sophisticated polling techniques, political advertising, staffing and support for writing the legislative outcomes desired by the policy demanders, the tools and trade of the money-media-election complex do their work. Directing access to these tools – and the money that buys them – is the means by which the electoral sphere is disciplined and safe candidates selected; first and foremost at the ballot access level.

This is the lynchpin; the root of the control system because allegiance will always be owed to the nominator! That boss will decide who sits at the table and what is open for discussion.

This is the lynchpin; the root of the control system because allegiance will always be owed to the nominator! That boss will decide who sits at the table and what is open for discussion.

How could this be changed? A civic assembly of the people – organized and understood as nominators – would shift allegiance to the people thus permitting an unregulated discourse – of the people’s design – which in turn would enable our electoral processes to become the medium they were meant to and must be.

Incumbent or aspiring elected officials, now beholden to the private policy demanders of the money-media-election complex – who now shepherd the nomination process – would shift to the public policy demanders – of/by and for the people; who could emerge, support, vote for, and directly nominate their candidates.

That was the original intent of this reform because there is and has to be a system; and a system will create particular certainties! In ours – a much decentralized and very democratic arrangement – it is certain

that allegiance will always be owed to the nominators and that wasn’t us!

Our absence ensured the old boss simply became the new one – the modern complex – and the money it dispenses is but one tool of its apparatus. It is an insufficient explanation for what truly drives our system and its dysfunctions; past or present. It is the complex’s’ overall management of electoral competition – maintaining an effective monopoly on the threat of its use – that offers a more complete understanding.

Much more than money alone, these factors essentially create “the means of exchange” for these modern-day powerbrokers.

Now the question becomes; what makes this strategy work?

What makes the strategy work, what fuels it is simple; our persistent absence from this process we were meant to own, and still can.

It’s is the public’s lack of attention to, and complete ignorance of our electoral architecture, and how it distributes power in our system, that enables a continuing ownership of our country by non-representative influences. Naturally, under these circumstances a vast and diversified people would be unable to develop strategies that could challenge the strong organization and steely resolve that prevails in any system of control; of any era.

Contrary to popular belief, politicians aren’t lazy; but the people are!

Without a wholly feasible strategy capable of channeling real power to the portion of the population with similar resolve, there is no alternative to being ruled.

For the American people, power in their system ultimately requires expression at elections – that they vote – but obviously it was never as simple as that. As we have learned- even our carefully crafted constitutional framework could not tame faction and corruption as the politics and sensibilities of the country developed.

But, what must be understood is that the central power that fueled those distortions derived from the most basic principle of popular elections; that was – and is – the authority to name the candidate standing for office.

The national implementation of open ballot access and the popular primary-nominating process was meant to give to the people the leverage previously enjoyed by the political powerbrokers, of all eras. But, absentee ownership cannot deliver on that leverage; wielding power is an everyday business and what this study leads to is clear.

In order to effectively exercise that power we must:

To achieve this would require:

Its byproducts would be:

It should now be indisputably clear that it is the intense policy demanders, of and behind the money-media-election complex, who participate in the nomination process and as result rule.

We have established however that the founding opportunity for self-government is genuine while it has also been demonstrated that in order to succeed it will be necessary for us to change.

It is also demonstrated that the change required is minimal; as will be the numbers of citizens necessary to effect it; but it must start with those of us that are ready to accept our own failures before blaming the “elites” of our control system. We have failed to analyze and understand. We have failed to demand from our sources of information and learning more and better.

It is also demonstrated that the change required is minimal; as will be the numbers of citizens necessary to effect it; but it must start with those of us that are ready to accept our own failures before blaming the “elites” of our control system. We have failed to analyze and understand. We have failed to demand from our sources of information and learning more and better.

Most importantly we have failed to participate effectively; individually and collectively. It is only this absence – of awareness and commitment – that has enabled the corruption of our past and the dysfunction and danger of the present.

It is a simple matter, now in the age of the Internet particularly, to overcome these difficulties and make the realization of our national concept and purpose practicable.

How this can be accomplished; what the Citizens Access Network makes possible and why, is, in its entirety, the message this website is devoted to delivering.